Tax Clearcuts. Reward Climate Smart Practices.

February 17, 2024

How forest carbon taxes can help slow and reverse deforestation and forest degradation across the US, and internationally

In a new study published in the journal Environment, Development, and Sustainability researchers at the Center for Sustainable Economy demonstrate how a tax on the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from industrial logging practices and clearing of forests for subdivisions can help slow and reverse deforestation and forest degradation and catalyze the transition to climate smart alternatives like long harvest rotations, ecological thinning of dense tree plantations, and establishment of forest carbon reserves. Across the four US states included in the study - Maine, North Carolina, Oregon and Washington - the researchers found that a forest carbon tax based on the social cost of carbon along with a number of tax credits and exemptions for good practices is likely to raise between $56 and $357 million per year for a Forest Carbon Incentive Fund used to acquire forestlands for public purposes, reduce the loss of forestland to developers, and compensate small forestland owners for the costs they face in making the climate smart transition. They also found that while the tax on clearcutting is likely to reduce profits for investor-owned forestlands somewhat, it would still leave an acceptable rate of return for "patient capital" investors like family offices, socially responsible investors, non-profits and sustainability fund managers.

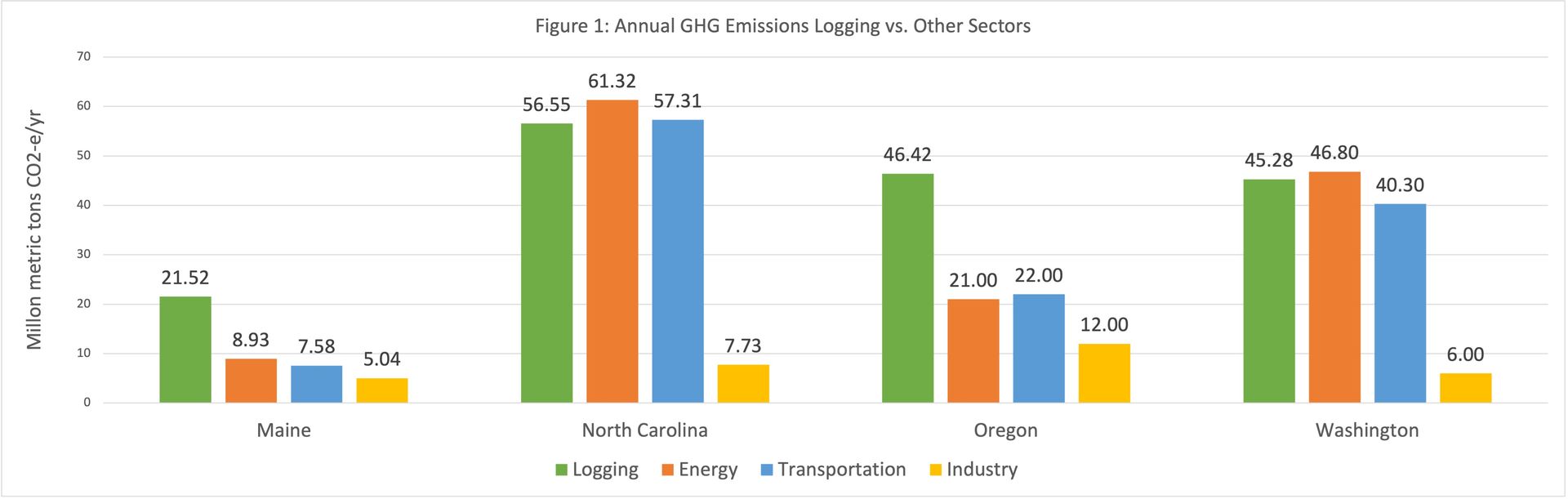

The study argues that the present GHG accounting system is flawed because it excludes GHG emissions from industrial logging activities and land development and that this gap has led to a corresponding policy vacuum. Despite the fact that the carbon footprint of a given year's logging activity is as significant as GHG emissions from sectors that are tracked (Figure 1), there remains no existing or proposed policy mechanism to reduce these emissions over time. Carbon taxes are one effective tool widely endorsed by economists that may do the trick. For GHG emissions from fossil fuels, policy makers at the state level have thus far opted for environmental trading schemes (i.e. cap and trade) over carbon taxes so perhaps for logging emissions a carbon tax could serve as the market-based mechanism of choice. Market based mechanisms are efficient because they are based on the concept of 'polluter pays,' which requires industries that pollute to pay for the damages and face the true costs of their activities.

The results of this study suggest that designing such a forest carbon tax and reward program is well within the capabilities of state forestry or air pollution agencies and can be implemented with existing sources of data and methods. It also finds that such a program can piggyback on timber harvest tax programs that already exist and so would not require significant new public funds for administration. Other key findings include:

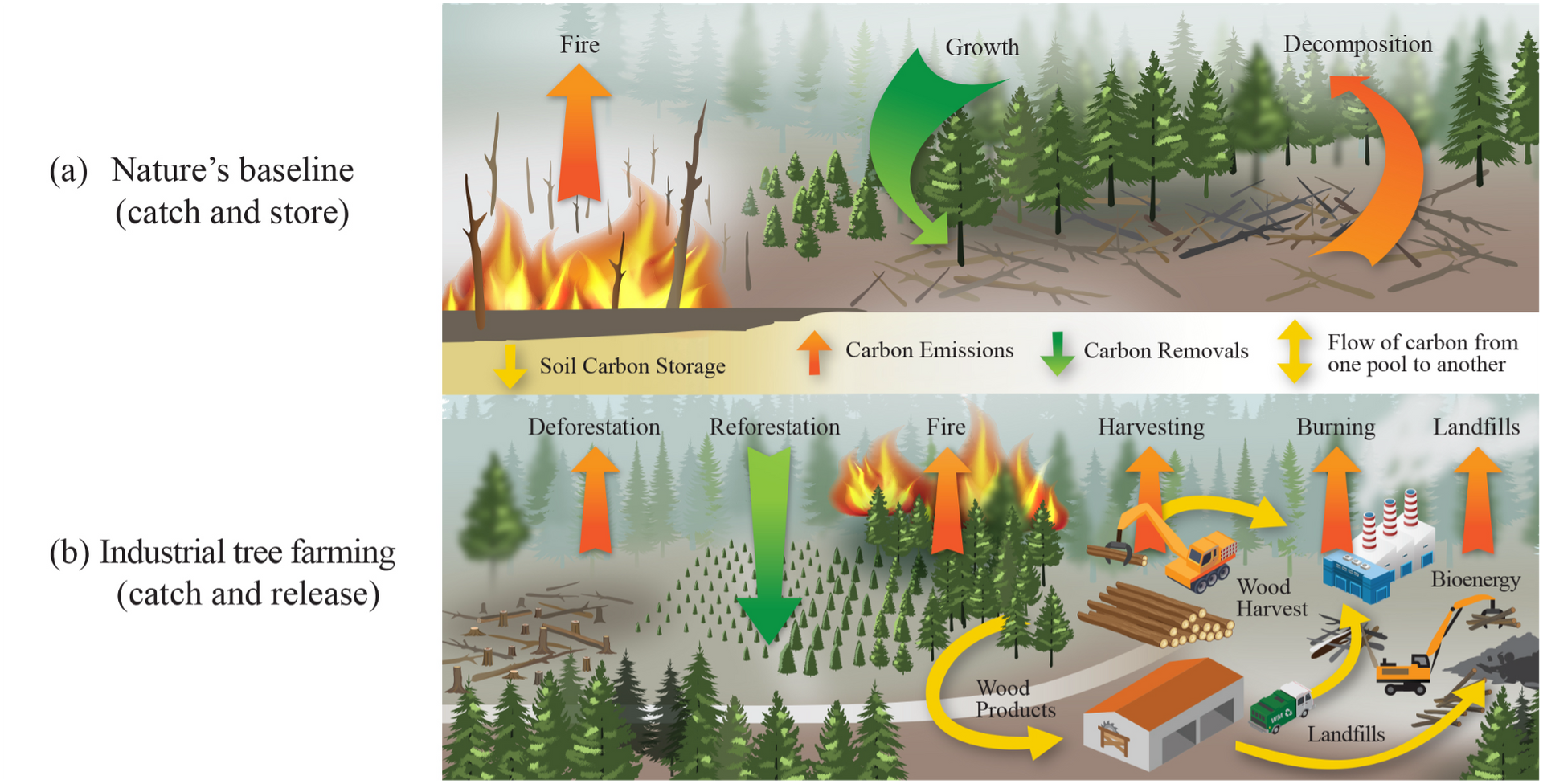

- Compared with the "catch and store" forest carbon cycle associated with natural forests, the "catch and release" carbon cycle on industrial forest landscapes results in greater carbon emissions, less carbon sequestration, less carbon storage, and greater vulnerability to climate stressors like wildfires, floods, and droughts (Figure 2).

- As a result, GHG emissions from industrial logging and land clearing should be accounted for under the same rules that apply to other sectors and not presumed to be offset by trees growing elsewhere or planted in the future. Any emissions offsets claimed by logging corporations should also be subject to the same rules facing fossil fuel emitters who must adhere to criteria such as permanence and additionality.

- Under the proposed forest carbon tax program, based on a draft legislative vehicle prepared for Oregon lawmakers, forestlands now managed under high-emissions-low-resiliency tree farming techniques would pay a gross carbon tax on the GHG emissions associated with any given volume of harvest but receive generous tax breaks and exemptions to adopt climate smart practices like long rotations, alternatives to clearcutting, and forest carbon reserves.

- Across the states, the study estimated the range of taxable GHG emissions to be 22 – 57 million metric tons carbon dioxide equivalent each year, with emissions factors of 0.91 – 2.31 tons carbon per cubic meter harvested, which translates to 9.29 – 16.74 tons CO2 per thousand board feet. These emissions factors are in remarkable agreement with factors estimated for tropical countries and suggest that logging in the US is just as carbon intensive, if not more, than logging tropical forests.

- Forestland cleared for subdivisions, strip malls, and highways is resulting in a steady and significant decline in carbon sequestration capacity, and a forest carbon tax can help steer development pressure to land that has already been cleared.

- A forest carbon tax can pay for big ticket items on each state's climate agenda. For example, the study estimates that annual forest carbon tax collections in Oregon (up to $347 million) can in one year enroll over 247,000 of non-industrial forestlands into a carbon payment program that would protect 42 million metric tons of CO2 over 30 years, according to a recent study by Portland State University. In Maine, a single year's tax collection ($56 million) could pay for conservation easements protecting over 150,000 acres now threatened by urban sprawl.

Please follow the links below for further reading:

- Read the paper online via Environment, Development, and Sustainability

- Download the paper in PDF format