How Trump’s Timber Trade War Can Benefit North American Forests

John Talberth • March 21, 2025

Carbon border adjustments on pulp and lumber could provide a rational basis

for tariffs and reduce high-emissions logging.

Most economists are appalled at any restraints to free trade, including tariffs. However, like any good thing, openness to international trade has declining returns of scale. Past a certain threshold, more trade openness causes more economic harm than good [1]. An economy too reliant on foreign countries for its goods, services, or investment capital suffers a host of socioeconomic ills caused by the inherent volatility of trade and the drain of manufacturing jobs, skills and knowledge that go with extreme specialization. Wise regulation of free trade, through strategic tariffs, can help reverse such trends and help communities rebuild the capacity to produce essential goods and services locally. Strategic tariffs can also be a tool to foster a race to the top in sustainable production and consumption [2]. But only if they are reconfigured for this purpose rather than existing merely as political weapons based on arbitrary tariff rates.

As an example, let’s take a closer look at the effects of the trade wars sparked by the Trump Administration on harmful logging activities in Canada and the U.S. As of this writing, the Administration has pledged to impose a 25% duty on all Canadian exports of pulp and lumber to the US in addition to a 14.5% tariff already in place [3]. This is a big deal for Canada. In 2023, Canada's wood product exports, a significant portion of which are softwood lumber, reached $13.6 billion, with the United States being the primary destination. Forest product exports represented 20% of BC’s total commodity export value. Canada is planning to retaliate with a 25% tariff of its own on US lumber imports, mostly softwoods. Canada is the largest US lumber export market, so this is also a big deal for the US.

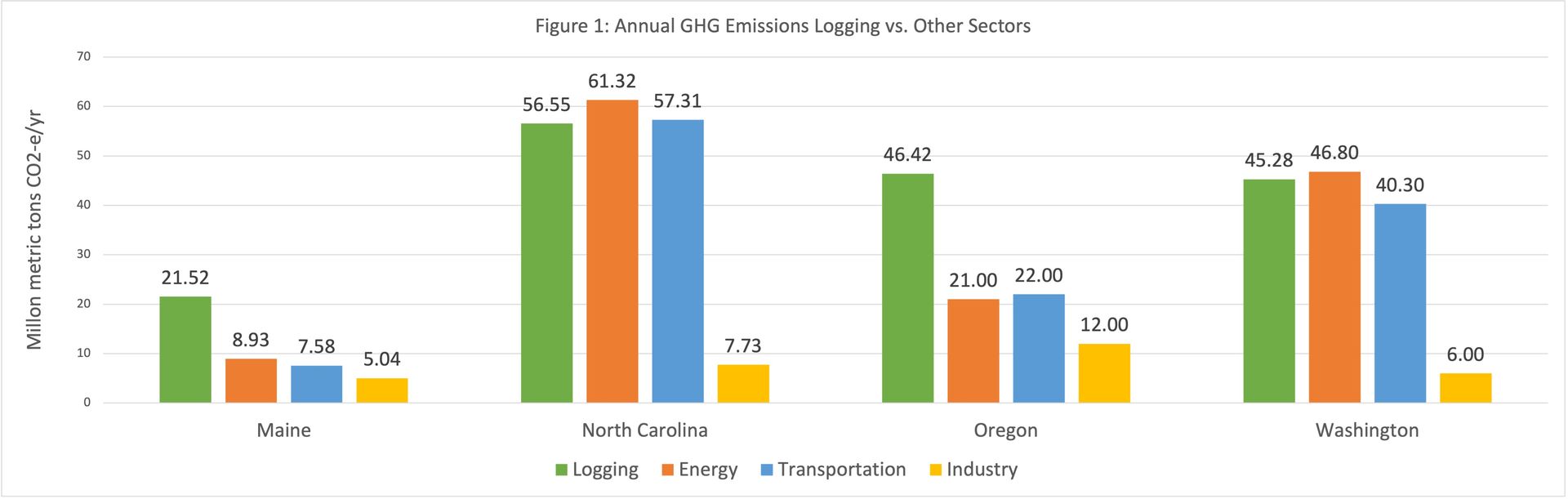

Despite the trade distorting effects of these tariffs, they can, in fact, be justified by market failures associated with industrial logging activities on both sides of the border. In the US, corporate logging practices like replacing real forests with monoculture tree farms, clearcutting, spraying of toxic chemicals and converting forestlands to urban sprawl have accelerated. Because of these stressors, only 28% of US forestlands exist in their natural state of ecological integrity [4]. In the lower 48, that figure falls to just 10% or less. If properly accounted for, the carbon emissions associated with this type of logging would be the number one or two source in a recent analysis of logging-related emissions in four states (figure below) [5].

In Canada, the logging and export of old growth forests from British Columbia and the rampant clearcutting of boreal forests for low end uses such as toilet paper have sparked a major backlash by conservation and scientific organizations. NRDC, for example, estimates that carbon emissions associated with clearcutting of boreal forests at a rate of approximately 1.3 million acres a year generates 80 million metric tons CO2-e [6].

A strategic tariff regime – one based on the externalities associated with deforestation and forest degradation – can play a role in reducing harmful practices and scaling up climate smart alternatives like long rotations (which reduces the annual rate of logging) and alternatives to clearcutting. It can help reduce competitive barriers to lower carbon substitutes like bamboo, green steel, and carbon negative concrete. How can this be operationalized? Here, carbon border adjustments (CBAs) can play a major role as a longer-term substitute for the haphazard tariffs now being imposed by both countries.

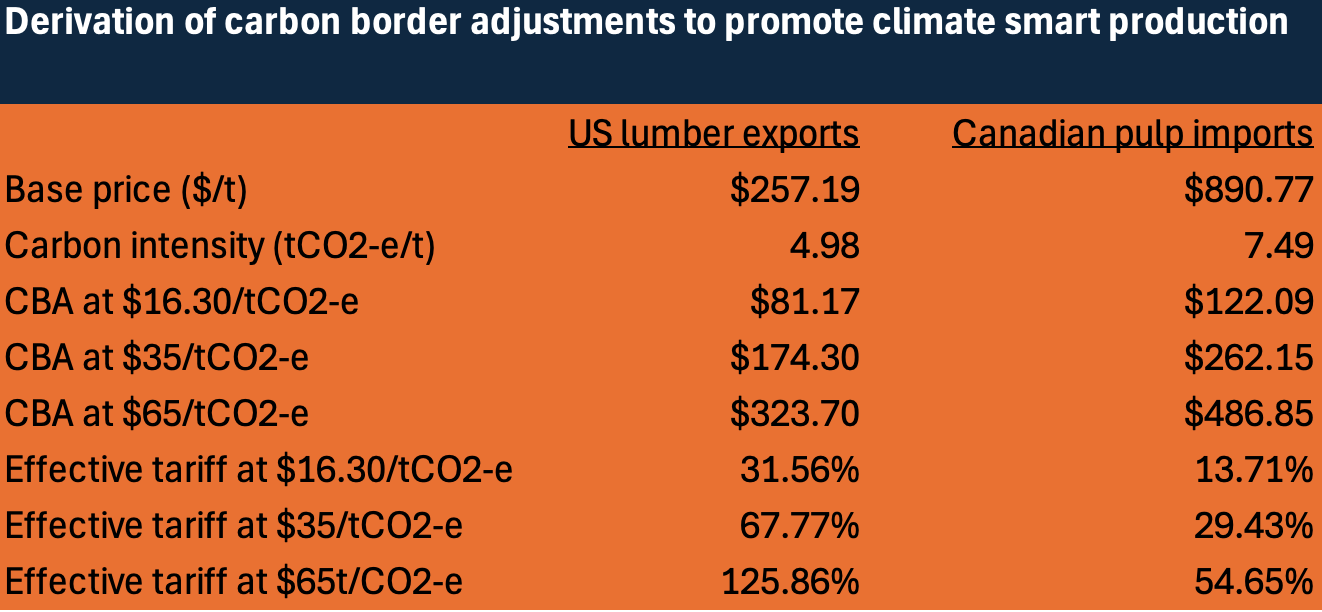

CBAs have received an increasing amount of attention in recent years in the EU and the US as a way to level the playing field with respect to the import of high-carbon commodities. A carbon border adjustment mechanism is a policy tool that aims to ensure imported goods face a carbon price equivalent to that of domestically produced goods, preventing carbon leakage. The EU first enacted its CBA mechanism in 2023 and is planning to supplement its list of commodities affected to include pulp, paper, biomass and lumber in the next year or two. In the US, four legislative proposals were introduced into the 118th Congress that provide a range of CBAs between $15 and $65 per metric ton CO2-e embodied in imported goods. It is useful to compare the effective tariff rate associated with these CBAs with what is currently being imposed by the tit for tat trade war between Canada and the US. The table below provides an overview.

The key to CBA rates is the carbon intensity of production, expressed as metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2-e) per ton of product. In a journal article released in 2024, CSE calculated the relevant carbon intensities for both short and long-lived wood products produced in Oregon, Washington, Maine and North Carolina [6]. The average across all states was estimated to be 4.98 tCO2-e for long lived products (i.e. lumber). In Canada, CSE calculated the carbon intensity of pulp exports using the data from one of the largest pulp operations there, which produces pulp for export to the US for manufacturing into tissue paper, paper towels, and diapers. In a forthcoming report, we estimate that the carbon intensity of pulp exports from Ontario is 7.49 tCO2-e [7].

In the table, three CBA levels are applied to these carbon intensities and then compared with current market prices to determine the effective tariff rate if the mechanism were the CBAs and not the political tariff rates now being imposed. CBA rates of $16.30, $35, and $65/tCO2-e, were modeled, with the $16.30 figure the actual effective carbon price in the US in 2025 while the latter two levels were taken from prospective legislation now before the 118th Congress. For Canadian pulp imports, the CBAs would result in effective tariffs of 13.71 – 54.65%, which is more or less in line with the current US tariff of 40% on imported pulp. For US lumber exports, a Canadian CBA of $16.30/tCO2-e would amount to a 31.56% tariff, a bit above the 25% retaliatory level but still within a reasonable range. Canadian CBAs of $35 and $65 would be prohibitive and greatly curtail US exports since the effective tariff rates would be 67.77 and 125.86%, respectively.

What this analysis demonstrates is that carbon border adjustments, if set based on rigorous life cycle analyses of carbon intensities, could be a workable substitute for the current, highly politicized regime of tariffs and counter tariffs now being pursued by both countries. It also demonstrates how CBAs can be used to help internalize the enormous, externalized costs associated with clearcutting and rapid logging of boreal and temperate forests on both sides of the border and incentivize climate smart alternatives that have lower carbon intensities.

References

[1] Talberth, J., Bohara, A., 2006. Economic openness and green GDP. Ecological Economics 58 (2006) 743 – 758.

[2] Hersh, A.S., Bivens, J., 2025. Tariffs – Everthing you need to know but were afraid to ask. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. Available online at: https://www.epi.org/publication/tariffs-everything-you-need-to-know-but-were-afraid-to-ask/.

[3] Stewart, P., 2025. Lumber Market Shifts: How New Tariffs Will Reshape the Industry. ResourceWise. Available online at: https://www.resourcewise.com/forest-products-blog/lumber-market-shifts-how-new-tariffs-will-reshape-the-industry.

[4] Grantham,H.S., Duncan, A., Evans, T.D., et al. (2021). Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity. Nature Communications https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. F.

[5] Talberth, J., Carlson, E., 2024. Forest carbon tax and reward: regulating greenhouse gas emissions from industrial logging and deforestation in the US. Environ Dev Sustain (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-04523-7

[6] Skene, J., Polanyi, M., 2021. Missing the Forest: How carbon loopholes for logging hinder Canada’s climate leadership. Washington, DC: Natural Resources Defense Council.

[7] Talberth, J., 2025. Boreal forests down the toilet. A life-cycle analysis of greenhouse gas emissions associated with pulp exports from Ontario, CA. Port Townsend, WA: Center for Sustainable Economy (in press).

Share Post

All Rights Reserved | Center for Sustainable Economy